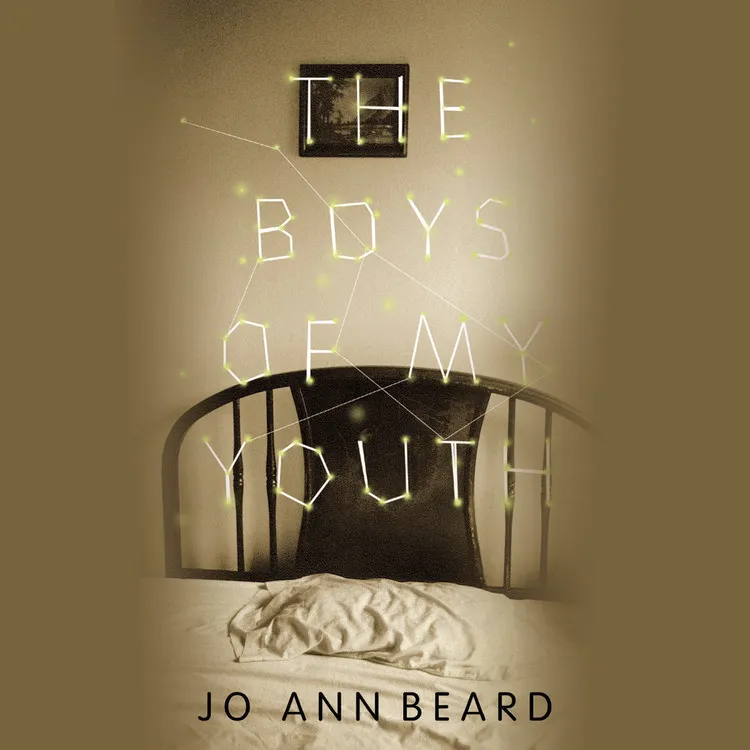

Review: The Boys of My Youth

Jo Ann Beard’s Rendering of How We Try to Grow Up

It’s all in the background. Â

In Jo Ann Beard’s 1998 memoir The Boys of My Youth, pristine physical descriptions and a wry sense of humor sit up front. Her writing is a virtuosic display of wit and attentiveness—a figure skater pirouetting flawlessly and awe-inspiring, haunting those of us in the bleachers with everything we will never do. Take her fireworks, painted as “long, terrible waterfalls of yellow and blue,†or her sun as it “hoists itself up and gets busy, laying a sparkling rug across the water, burning the beads of dew off the reeds, baking the tops of our mothers’ heads.†The power of her prose lies in revealing what exists beneath perception, in presenting how the same tree, lake, or conversation can be experienced with near complete disparity depending on which setting our emotional lens happens to be caught.Â

Yet, for all this windshield-wide beauty, in the backseat are unruly children of despair—hot and sweaty, unable to sit still or quiet for any significant length of time. Their presence is like eyes drilling into the soft spot on the back of the skull, pulling at the threads of our attention with pure, undiluted reactions to whatever stimuli seems, at that moment, to be the end of the world (though, of course, it never is; the end of the world won’t feel that bad).Â

Through thirteen essays, Beard recounts her childhood summer trips to Grandma’s—“From far away the idea of their house was magical to me, all those nooks, all those crannies, all those things to play with.†She reflects on teenage parties on PCP-laced weed—“I stretch out on my back, using a stack of magazines for a pillow, and crawl inside the music.†She shares the frustrations of home renovation with a perfectionist partner—“You try a different technique than he showed you and suddenly the longest piece has become divorced from itself. Oh dear.†And she recalls sensory memories of legs sticking to leather on a solo road trip—“I sat on my haunches in Key West, writing and seething and striking up conversations with strangers.â€

Alongside these central narratives of an average middle-class life, inconvenient sadness bubbles up: a marriage disintegrating, an alcoholic father, the death of a distant mother, and a nagging sense of always being slightly outside of others. With a firm grip, Beard highlights our tendency to invent exponential stabilizing handles—the funhouse octagon of self-reflection, where each mirror targets ever-new issues demanding our immediate attention—when we aren’t ready to admit what we actually need to let go of is that thing (you know the one) we claim we can’t exist without.

As in real life, or at least my own, losses and pains hover—bumming smokes, basking in the shade of each sunny day, out of sight but never too far. One can be happy, or at least hopeful, and still be affected by the past. Beard understands that the potency of primary relationships color in every experience; peripheral knowledge writes novels, or more aptly, memoirs.Â

Decay is uniform, tedious, and unremarkable in its return to dust. A life falling apart, though somewhat romantic when being engulfed by the blue-white tips of the flames, remains banal in its finality. No matter how grandiose the destruction, a single conclusion is reached: nothing left. The Boys of My Youth reminds us that the dirt will always be there, right under our feet, loyal and waiting, but the sky—the sky can be anything, a fresh canvas unrolled each moment, from a “pale peach burst†to “black and glittering with pinholes.†The earth is moving, even when we are unable, and though it may feel impossible, it really is this simple: try to look down a bit less and up a bit more.

Your words have the power to transport the reader, making them see the world from a perspective they hadn’t considered before.